Biodiversity is referred to as the diversity of plant and animal species in a specific habitat. The two main factors that make up biodiversity are species evenness and species richness.

India is renowned for having a diverse ecosystem, and 23.39% of its land is covered in trees and forests with nearly 91,000 identified animal species and 45,500 documented plant species.

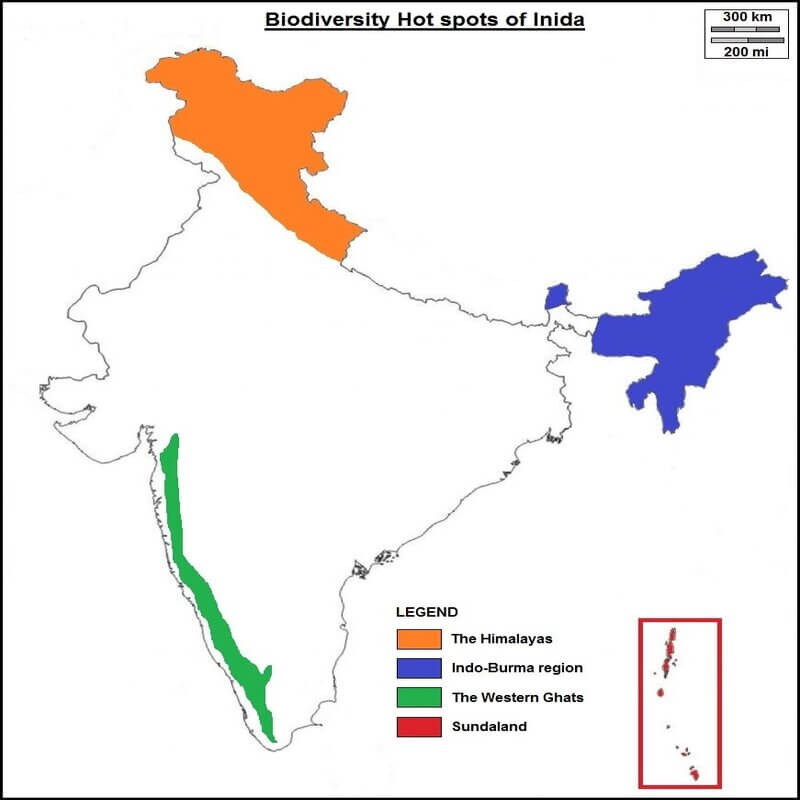

Four of the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots are located in India: The Himalayas, Western Ghats, Indo-Burma area, and Sundaland. Two of these, the Indo-Burma area and Sundaland, are distributed throughout South Asia and are not precisely contained within India’s formal borders.

What are Biodiversity Hot Spots?

The word “hotspot” describes regions with a high priority for conservation because of their abundant biodiversity, high endemism, and significant vulnerability. Hotspots for biodiversity are places with a high concentration of indigenous species.

In the case of marine hotspots, fish, snails, lobsters, and coral reefs are all taken into account.

Most hotspots are found in tropical and subtropical areas, where high temperatures and humidity are typical all year round.

With an elevation above sea level and ocean depth, animal diversity and ecosystem diversity change.

Only 2.5 per cent of the Earth’s land surface is taken up by the 36 hotspots that exist today, yet they are home to about 43 per cent of the world’s bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species, as well as more than half of its plant species.

Criteria to be satisfied for a biodiversity hotspot

A region must satisfy two strict requirements in order to be considered a biodiversity hotspot:

- Include at least 1,500 vascular plant species that are unique to the planet (known as “endemic” species).

- Have lost the majority of their native vegetation by at least 70%. In other words, it must be threatened.

Who Declares Biodiversity Hotspots?

Hotspots were first defined and promoted by Conservation International. Conservation International was founded in 1989, just one year after scientist Norman Myers published the article that popularised the idea of safeguarding these beautiful places.

Biodiversity Hot Spots in India

There are four Biodiversity Hotspots in India:

- Himalaya

- Indo-Burma

- Western Ghtas

- Sundaland

Himalayas

All of the world’s mountain peaks higher than 8,000 meters, including Mt. Everest (8,849 metres), are found within the Himalayan hotspot, which spans more than 3,000 kilometres across northern Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, and the northwest and northeastern states of India. It also has several of the deepest river gorges in the world.

The Himalayan Mountain range is nearly 7.5 million square kilometres in size and is divided into the Eastern Himalaya, which includes parts of Nepal, Bhutan, the northeastern Indian states of West Bengal, Sikkim, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh, and the Western Himalaya, which includes parts of Kumaon-Garhwal, northwest Kashmir, and northern Pakistan.

The Himalayan mountains are home to a variety of ecosystems, including :

- Mixed conifer and conifer forests in the higher hills

- Alpine meadows above the tree line, the tallest alluvial grasslands in the world

- Subtropical broadleaf forests along the foothills

- Temperate broadleaf forests in the mid hills

Even at heights higher than 6,000 meters, vascular plants have been discovered. Numerous big bird and mammal populations, including vultures, tigers, elephants, rhinos, and wild water buffalo, can be found in the hotspot.

The worldwide hotspot regions were reviewed and revised in light of species distribution, threats, and changes in threat status. The Himalayan hotspot was delineated and identified as separate from the Indo-Burma hotspot.

Threats to Himalayan Biodiversity

- Promoting both outside immigration and internal migration and leading to an exponential increase in the human population in some of the locations with the greatest biodiversity.

- Due to widespread legal and illegal logging, especially on steep slopes, as well as the substantial removal of forests and meadows for farming, there has been serious erosion.

- During the summer, the area is frequently burned to make way for livestock, which provides an extra hazard to the forest because fires can occasionally go out of control.

- Rapid deforestation and habitat fragmentation were the results of the conversion of forests and grasslands for agriculture and settlements, mainly in Nepal and the Indian states of Sikkim, West Bengal (Darjeeling), and Assam.

- Additionally, certain forest ecosystems have been severely harmed by anthropogenic activities such as domestic cattle overgrazing, overharvesting plants for traditional medicine, collecting fuel wood, and extraction of non-timber forest products.

- Unplanned and poorly managed tourism operations exacerbate environmental damage.

- In the Himalayas, illegal poaching is a significant problem; tigers and rhinoceroses are targeted for their body parts for use in traditional remedies, whilst snow leopards and red pandas are targeted for their stunning pelts.

Indo-Burma

The Indo-Burma hotspot is the largest of the world’s 36 recognised hotspots, covering a total area of 2,373,000 km2.

The Indo-Burma hotspot formerly encompassed parts of northeastern India, Bangladesh, and Malaysia.

However, Bangladesh, India, and Malaysia are regarded as extralimital to the hotspot for the purposes of the ecosystem profile because northeastern India is included in the Himalayan hotspot and the hotspot only barely extends into Bangladesh and Malaysia.

The hotspot has an incredible geographic diversity, ranging from the tallest peak in Southeast Asia to coastlines along the Bay of Bengal, Andaman Sea, Gulf of Thailand, and South China Sea.

Along with several of Asia’s greatest rivers and their lush floodplains and deltas, it also comprises the eastern extensions of the Himalayas, remote massifs, and plateaus.

Due to the diversity of its landforms and climatic zones, the Indo-Burma hotspot supports a wide range of habitats and, as a result, a high level of overall biodiversity.

In the past 12 years, six new species of big mammals have been identified in this area:

- Large-antlered Muntjac

- Annamite Muntjac

- Grey-shanked Douc

- Annamite Striped Rabbit

- Leaf Deer

- Saola

The majority of the endemic freshwater turtle species found in this hotspot are in danger of going extinct because of overfishing and habitat destruction.

The severely endangered White-eared Night-heron, Grey-crowned Crocias, and Orange-necked Partridge are among the 1,300 bird species that exist.

The hotspot’s most diverse ecosystems are its forests. From evergreen forests with a great diversity of canopy tree species to semi-evergreen and mixed deciduous forests with few tree species, the hotspot supports a wide range of forest types.

The hotspot’s limestone karst formations are home to extremely rare ecosystems with high levels of endemism, especially in plants, reptiles, and molluscs—species that are entirely unique and are found nowhere else.

Threats to Indo-Burma

Indo-Burma is one of the top five most endangered biodiversity hotspots, according to Conservation International, due to the rate of resource extraction and habitat loss.

- The greatest threats to this hotspot’s biodiversity are logging, over-exploitation of natural resources, industrial agriculture, trade and consumption of wildlife, the building of massive infrastructures including dams, highways, and ports, and climate change.

- In Indo-Burma, commercial timber exploitation ranks second among the causes of deforestation.

- The loss of habitat has had an effect on other landforms, including wetlands and freshwater floodplain swamps.

- Large tracts of mangroves have been contained within aquacultural ponds, and many rivers have been dammed and altered.

- Mangroves, lagoons, marshes, and other natural wetlands, including several Ramsar sites in the hotspot’s coastal zones, have undergone substantial conversion into shrimp and fish farms or have been removed for charcoal and fuelwood.

Western Ghats

The Western Ghats sometimes referred to as the Sahyadri Hills locally, are made up of the Malabar Plains and a group of mountains that extend 30 to 50 kilometres inland and parallel to India’s western coast.

With just the 30 km Palakkad Gap in between, they span 1,600 km from the southernmost point of the nation to Gujarat in the north, covering an area of over 160,000 km2.

By blocking the southwestern monsoon winds, the Western Ghats control the amount of rain that falls on peninsular India.

Every year, a lot of rain falls on the western slopes of the mountains, with most of it falling during the southwest monsoon between June to September.

Rainfall drops off as you move from south to north, while the eastern slopes are drier.

Numerous rivers, including the three main eastward-flowing rivers on the peninsula, originate in these highlands. As a result, they serve as essential sources of power, irrigation, and drinking water.

There are many different types of vegetation in the Western Ghats due to the region’s complicated geography and varying rainfall patterns.

They include scrub forests in low-lying rain shadow regions and on the plains, deciduous and tropical rainforests up to a height of roughly 1,500 m, and an exceptional mosaic of montane forests and rolling grasslands above that altitude.

Threats to the Western Ghats

- The forests of the Western Ghats have been heavily fragmented and selectively cut across their whole range.

- For monoculture plantations of tea, coffee, rubber, oil palm, teak, eucalyptus, and wattle as well as to make room for reservoirs, highways, and railways, forests have been removed.

- More forests are lost due to encroachment into protected areas. On slopes that were once covered in forest, cattle and goat grazing inside and close to protected zones severely erodes them.

- The majority of the remaining forest cover is made up of disturbed secondary growth or wood plantations.

- Intense hunting pressure, fuelwood extraction, and the harvesting of non-timber forest products are placed on the few surviving forest sections.

- Other concerns include unrestrained tourism and forest fires.

- The conflict between humans and wildlife has increased as a result of population growth in protected zones and other woods. In an effort to stop more harm, wild animals are routinely killed or hurt, and farmers are typically under-compensated.

Sundaland

The Sundaland hotspot includes the western half of the Indo-Malayan archipelago, which is made up of about 17,000 equatorial islands. Borneo (725,000 km2) and Sumatra are two of the largest islands in the world (427,300 km2).

Almost all of Malaysia including Peninsular Malaysia and the East Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah in northern Borneo, Singapore at the tip of the Malay Peninsula, Brunei Darussalam, and the western half of Indonesia, including Kalimantan, are included in Sundaland. A small portion of southern Thailand the provinces of Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat is also included the Indonesian portion of Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and Bali.

India is in charge of the Nicobar Islands, which are also included.

The 7,100 islands of the Philippines Hotspot are direct to the northeast of Wallacea, which is separated from Sundaland Hotspot by the renowned Wallace’s Line.

Threats to Biodiversity in Sundaland

- The stunning flora and wildlife of the Sundaland Hotspot are being rapidly destroyed by industrial forestry on these islands

- Global traffic in animals, uses tigers, monkeys, and turtle species for food and medicine in other nations.

- Only in this area are orangutans located, and their population is rapidly declining.

- The Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra are also home to some of the final refuges for two Southeast Asian rhino species.

- Like many other tropical regions, the forests are being destroyed for business.

- The production of pulp, oil palm, and rubber are three of the most harmful factors endangering biodiversity in the Sundaland Hotspot.

Conclusion

India is renowned for having the world’s richest flora, with over 18000 species of blooming plants, and has a diverse climate, topography, and habitat. Three thousand different plant species can be found in India’s eight primary floristic zones, which are the Western and Eastern Himalayas, the Indus and Ganges, Assam, the Deccan, Malabar, and the Andaman Islands.

The good climatic conditions, fertile soil, suitable temperature, and an abundance of precipitation, which promote the growth of numerous plants, are the causes of the vast diversity of Indian biodiversity hotspots. These regions are heavily wooded, with savanna grasslands and tropical and subtropical forests.

They are distinguished by the nation’s largest rivers, have rich alluvial soil, and can therefore support a wide variety of animals and plants. In terms of ecology and energy production, these regions are incredibly productive.

Article written by Aryadevi E S

Leave a Reply