What is the Southern Ocean Carbon Anomaly? Why does it defy the Climate Models? Read here to learn all about the phenomenon.

A recent study published in Nature Climate Change has revealed that the Southern Ocean has absorbed more carbon dioxide since the early 2000s, contrary to long-standing climate model predictions.

This unexpected behaviour, termed the Southern Ocean carbon anomaly, highlights a critical gap between observed climate processes and model projections, with profound implications for global climate mitigation strategies.

What is the Southern Ocean Carbon Anomaly?

The Southern Ocean carbon anomaly refers to the continued strengthening of the Southern Ocean as a carbon sink, despite climate models predicting that it would weaken and begin releasing CO₂ under global warming.

- Climate models expected stronger winds to bring CO₂-rich deep waters to the surface, causing outgassing

- Instead, observations show increasing carbon absorption, defying theoretical expectations

This makes the Southern Ocean a temporary but fragile buffer against climate change.

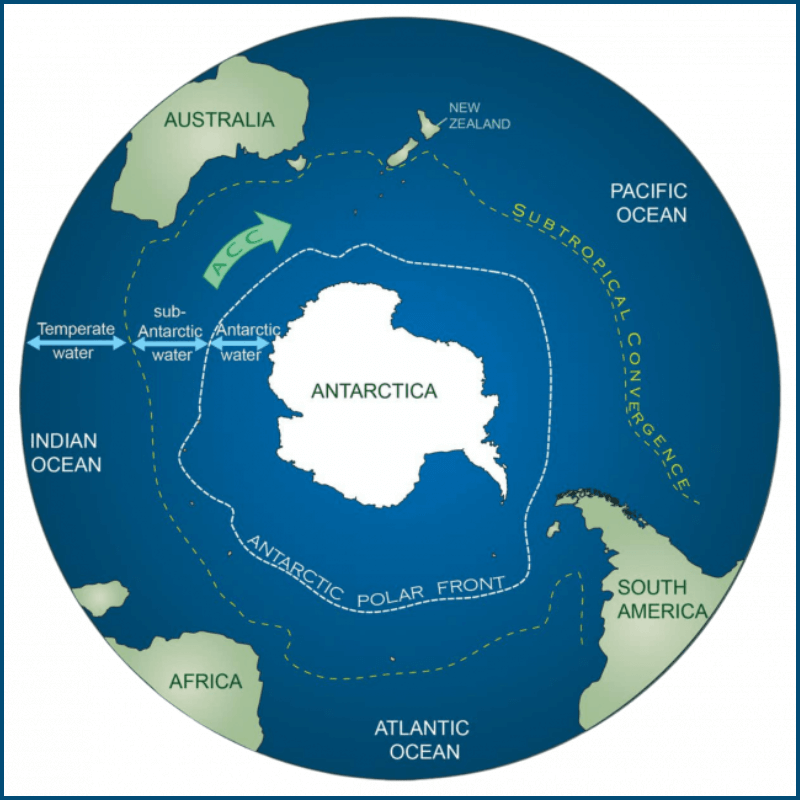

Why the Southern Ocean Matters

The Southern Ocean plays a disproportionately large role in regulating Earth’s climate:

- Covers only ~30% of the global ocean area

- Absorbs ~40% of anthropogenic oceanic CO₂ uptake

- Acts as a key connector between surface waters and deep ocean carbon storage

Any shift in its behaviour has global climate consequences.

Mechanism Behind the Carbon Anomaly

Expected Model Behaviour (Earlier Understanding):

- Climate change led to stronger Southern Hemisphere westerly winds

- Winds enhance the upwelling of carbon-rich circumpolar deep waters

- Upwelled CO₂ reaches the surface and is released into the atmosphere

- Result: Weakening carbon sink

Observed Reality (Anomalous Behaviour):

Despite stronger winds, CO₂ release has not occurred. Instead, the following processes dominate:

Key Physical Processes Driving the Anomaly

- Freshwater Input from Antarctica

- Accelerated glacial melt and increased precipitation

- Adds freshwater to surface layers

- Freshwater is less dense, making surface waters more buoyant

- Enhanced Stratification

- Fresh, light surface waters sit atop warmer, saltier deep waters

- Vertical mixing is suppressed

- Formation of a stratified surface “lid”

- Trapping of Carbon-Rich Deep Waters

- Upwelled circumpolar deep waters remain 100-200 metres below the surface

- CO₂-rich waters fail to reach the air–sea interface

- Prevents expected CO₂ outgassing

- Reduced Air–Sea Gas Exchange

- Stratification blocks effective exchange between the ocean and the atmosphere

- Net effect: continued carbon absorption

Role of Small-Scale Ocean Processes

- Ocean eddies redistribute heat and freshwater

- Ice-shelf cavity dynamics influence freshwater release

- These fine-scale processes amplify stratification but are:

- Poorly resolved in coarse global climate models

- Underrepresented in long-term projections

Why Climate Models Failed to Predict This

- Inadequate resolution of mesoscale eddies

- Simplified representation of freshwater dynamics

- Sparse observational data from polar regions

- Poor integration of ocean chemistry-physics interactions

This exposes a structural blind spot in climate modelling.

Implications of the Southern Ocean Carbon Anomaly

- Temporary Climate Buffer

- Slows atmospheric CO₂ accumulation

- Masks the full impact of global emissions

- Provides illusory breathing space, not a solution

- Risk of Abrupt Reversal

- Observations suggest surface stratification is thinning

- If the freshwater “lid” collapses:

- Stored deep-ocean carbon could rapidly escape

- Triggering a positive climate feedback loop

- Limits of Natural Carbon Sinks

- Ocean sinks are dynamic and unstable

- Cannot be relied upon as permanent mitigation tools

- Reinforces the need for direct emission reductions

- Policy and Climate Governance Implications

- Undermines over-reliance on nature-based solutions

- Highlights uncertainty in long-term carbon budgets

- Strengthens the case for:

- Precautionary climate action

- Conservative emissions pathways

- Imperative for Sustained Observation

- Southern Ocean remains one of the least observed regions

- Requires:

- Year-round monitoring

- Autonomous floats (e.g., Argo)

- Satellite-in situ data integration

Way Forward

- Improve Climate Models

- Incorporate fine-scale ocean processes

- Better representation of freshwater fluxes

- Integrate ocean biogeochemistry with physics

- Expand Polar Observation Networks

- Continuous monitoring of stratification and carbon fluxes

- Investment in polar research infrastructure

- Global data-sharing mechanisms

- Strengthen Emission Reduction Commitments

- Treat natural sinks as uncertain buffers

- Accelerate decarbonisation of energy and industry

- Align policies with worst-case climate scenarios

- Integrate Ocean Feedbacks into Climate Policy

- Include ocean uncertainty in global stocktake exercises

- Adjust carbon budgets for potential sink collapse

- Enhance climate risk communication

Conclusion

The Southern Ocean carbon anomaly demonstrates that Earth’s climate system can temporarily defy expectations, but not indefinitely. Freshwater-driven stratification has masked deeper vulnerabilities, delaying but not eliminating climate risk. If this protective layer weakens, the Southern Ocean could rapidly shift from a carbon sink to a climate amplifier.

This phenomenon underscores a critical lesson for climate governance: natural buffers are finite and fragile. Only sustained emissions reduction, robust climate modelling, and comprehensive observation can prevent abrupt and irreversible climate feedbacks.

Related articles:

Leave a Reply