The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway running north to south across the Isthmus of Suez in Egypt to connect the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. The Suez Canal is one of the most important waterways in the world. Read here to know all about it.

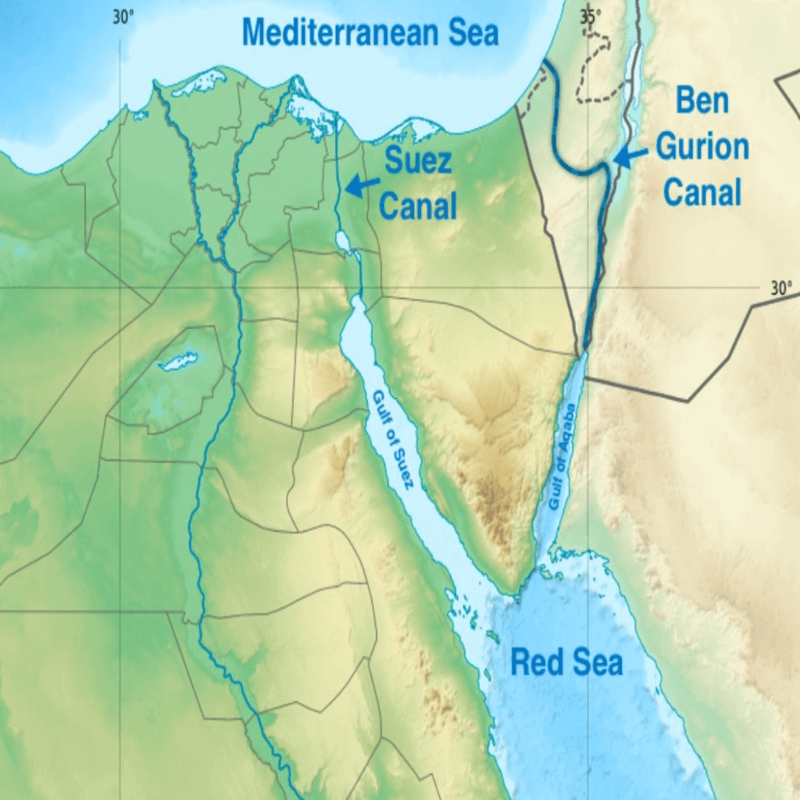

Recently, there has been renewed interest in the Ben Gurion Canal Project, a proposed 160-mile-long sea-level canal that would connect the Mediterranean Sea with the Gulf of Aqaba, bypassing the Suez Canal.

The new canal was conceptualized in the 1960s to create an alternative maritime route connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean, bypassing the Suez Canal.

The aim is to challenge Egypt’s monopoly in global maritime dynamics.

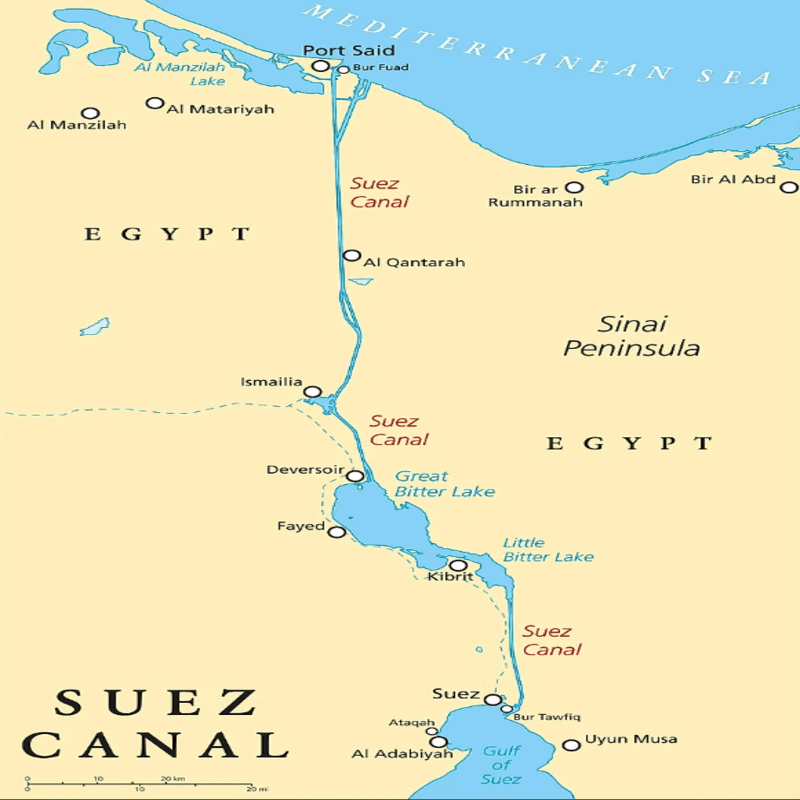

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal separates the African continent from Asia, and it provides the shortest maritime route between Europe and the lands lying around the Indian and Western Pacific oceans. It is one of the world’s most heavily used shipping lanes.

- The canal is extensively used by modern ships, as it is the fastest crossing from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean. Tolls paid by the vessels represent an important source of income for the Egyptian government.

- A railway and a sweet water canal are run on the west bank parallel to the Suez Canal.

- The Canal runs between Port Said harbor and the Gulf of Suez, through soils that vary according to the region.

The dredging of the canal took almost 10 years using Egyptian labor, and it was opened for navigation for the first time on 17 November 1869.

The idea of a canal connecting the Mediterranean and Red Seas dates back to ancient times. However, the modern construction of the Suez Canal was undertaken by the French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps. Construction began in 1859 and was completed in 1869.

Read: Major Straits in the World

History of the Suez Canal

It is an accepted historical fact that the Egyptian Pharaoh Senausert III of the Twelfth Dynasty was the first to devise the notion of linking the Red Sea and the Mediterranean through the Nile and its branches.

This served to encourage commerce and ease contact between the East and the West as ships arrived from the Mediterranean, traveled up the Nile to Zagazig, and then used the Bitter Lakes, which at the time were connected to the Red Sea, to reach the Red Sea. Remains of that canal may now be discovered in Geneva, which is close to Suez.

The Canal was left for sand deposition and a dam was formed, thus, isolating the Bitter Lakes; which suffered from the absence of maintenance for a very long time, from the Red Sea.

- In 610 BCE Necho II (also known as Nekós) did everything in his tried to re-dig the Canal, but only managed to connect the Bitter Lakes to the Nile failing to connect them to the Red Sea.

- In 510 BCE, Darius I reconnected the Bitter Lakes and the Nile, but, like his predecessor, failed to connect them to the Red Sea except via small canals not suitable for navigation except during the flood season of the Nile.

- In 285 BCE Ptolemy II managed to overcome all the challenges that faced his predecessors as he restored navigation to the entire Canal after successfully digging the part between the Red Sea and the Bitter Lakes to replace the small unnavigable canals.

- in 98 CE, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Trajan, there was a need for the Canal for trade purposes so he re-dug it. It started in Cairo; at the bay mouth, and ended in El-Abbasa where it connects to the old Nile branch in Zagazig.

- The Byzantines (circa 400 CE) neglected the Canal completely until it became unnavigable due to sand deposition.

- In 641 CE Amr Ibn El-A’as reopened the Canal for navigation and named it the Amir El-Mo’menin Canal.

- By 760 CE, the Abbasid Caliph, Abu Jafar El-Mansur, ordered the Canal be filled with sand so as not to be used in the transport of supplies to the people of Mecca and Medina who rebelled against his rule.

The navigation between the two seas stopped for approximately eleven centuries during which land routes were used to transport Egyptian trade.

In 1820, Mohammad Ali Pasha ordered part of the Canal be fixed for irrigation purposes of the lands between El-Abbasa and El-Qassasin.

The Suez Canal’s actual history starts with the First Concession; and the other concessions that followed to the groundbreaking then the completion of the digging on August 18th, 1869, and the inauguration ceremony on November 17th, 1869.

- The first concession, which granted Ferdinand de Lesseps the right to establish a company responsible for digging the Suez Canal, was issued on November 30th, 1854.

- The second concession was issued on January 5th, 1856.

- The Universal Company of the Maritime Canal of Suez was established on December 5th, 1858.

- The digging started on April 25th, 1859 despite objections from Britain and the Ottoman Empire.

The Suez Canal was initially owned and operated by the Suez Canal Company, which was a French and Egyptian venture. However, due to financial difficulties, Egypt sold its shares to the United Kingdom in 1875, making the canal an international waterway.

1882: The British successfully managed to occupy Egypt after the Urabi Revolt, seized the Company’s facilities, and stopped traffic through it for some time.

1888: The Constantinople Convention- An agreement was made between France, Austria, Hungary, Spain, Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, and Turkey to draw a final system that ensured freedom of navigation through the Suez Canal.

Suez crisis

The Suez Crisis was a pivotal event in the canal’s history.

In 1956, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the canal, leading to a crisis involving the United Kingdom, France, and Israel.

The crisis resulted in military intervention by these nations, but due to international pressure, they eventually withdrew.

The United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) was deployed to supervise the withdrawal of foreign troops, and Egypt resumed control of the canal.

Read: Crossroads 1960-1970

Six-Day War (1967) and Closure

During the Six-Day War in 1967, the Suez Canal was closed by Egypt, and its blockade continued for several years. The closure significantly impacted global shipping and trade routes.

The Suez Canal was reopened in 1975, and efforts have been made to modernize and expand its capacity.

In 2015, Egypt inaugurated the New Suez Canal, a major expansion project aimed at increasing the canal’s capacity and allowing for the simultaneous passage of ships in opposite directions.

The Ever Given mishap

In March 2021, the large container ship Ever Given became lodged across the Suez Canal, blocking one of the world’s most crucial waterways for nearly a week.

The blockage of the Suez Canal had a significant impact on global trade, as the canal was a key route for approximately 12% of the world’s trade. Hundreds of vessels, including container ships, oil tankers, and other cargo vessels, were stranded on both ends of the canal, waiting for the Ever Given to be refloated.

The incident highlighted the vulnerabilities of global shipping routes and supply chains. It prompted discussions about the need for improved navigation and safety measures in key waterways. The crisis also led to increased scrutiny of large container vessels and the potential risks associated with their size.

Importance of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is strategically located, providing a direct and time-saving maritime route between Europe and the Indian Ocean.

Ships using the canal avoid the lengthy and perilous journey around the southern tip of Africa, known as the Cape of Good Hope, which significantly reduces transit times and fuel consumption.

- Approximately 12% of the world’s trade passes through the Suez Canal. It is a major conduit for container ships, bulk carriers, oil tankers, and other vessels, facilitating the transportation of goods, commodities, and energy resources between major global markets.

- It allows ships to cut transit times and operational costs compared to alternative routes. For example, a voyage from Europe to India or East Asia through the Suez Canal is significantly shorter than the alternative route around Africa.

- The Suez Canal is a key route for the transportation of energy resources, especially oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Is there a need for an alternate route?

Despite its importance, the Suez Canal’s vulnerability to blockages, accidents, or geopolitical tensions underscores the need for alternative routes and diversification in global maritime trade.

- The Suez Canal is a narrow passage, and incidents like ship groundings or blockages can disrupt the flow of maritime traffic. The Ever Given incident in 2021 highlighted the potential risks associated with relying heavily on a single key waterway.

- Geopolitical factors, such as conflicts or changes in governance in the region, can impact the security and accessibility of the Canal.

- Diversifying trade routes by developing and utilizing alternative pathways, such as the Northern Sea Route (Arctic route) or the Cape of Good Hope, can enhance resilience in the face of unforeseen disruptions.

Ben Gurion Canal Project

Named after Israel’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion, the idea originated in the 1960s as an alternative maritime route connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean, bypassing the Suez Canal.

- The idea is to cut a canal through the Israeli-controlled Negev Desert from the tip of the Gulf of Aqaba – the eastern arm of the Red Sea that juts into Israel’s southern tip and south-western Jordan – to the Eastern Mediterranean coast.

- It will create an alternative to the Egyptian-controlled Suez Canal that starts from the western arm of the Red Sea and passes to the southeastern Mediterranean through the northern Sinai Peninsula.

There are suggestions that Israel wants to seize control of Gaza and destroy Hamas to take advantage of the canal’s economic potential.

The Ben Gurion Canal Project would significantly affect geopolitics and international trade if it were to be constructed. By avoiding the Suez Canal and opening up a new maritime route between Europe and Asia, it would lessen Egypt’s influence over international commerce.

Read: Global Trade Disruptions

-Article by Swathi Satish

Leave a Reply