Once the British gained power, She introduced many changes in the Economic, Political, and Social spheres. Learn more.

Once the British gained power, She introduced many changes in the Economic, Political, and Social spheres. Learn more.

We have seen that India in the 1750s saw the decline of the Mughal Empire and the emergence of Successor States.

The British who came to India for trade become the rulers of territories.

They introduced many changes disrupting the economy, polity, and society.

- Economy: The British policies towards agriculture and industry were mainly aimed at their benefit. This resulted in the commercialisation of agriculture and the ruin of traditional Indian industries.

- Polity: Various Acts passed by the English had positive and negative outcomes. However, the most significant result of the new laws was the enforcement of the British authority over the Indian mainland. New laws like the Regulating Act of 1773, Pitts India Act of 1784, various Charter Acts etc led to constitutional development. On the administration part, too various changes were introduced – particularly the revenue administration, civil services, police, army, and judicial services.

- Society: British policies towards education, language, and culture resulted in significant transformation in Indian society. While the positive changes were welcomed by Indian society, the oppressive measures resulted in revolts and rebellions.

We will be covering each of these details in subsequent posts. In this post, we mainly concentrate on the changes made by the British from a broad perspective covering rural India as well as urban India.

Also read: Administrative Organization During British Rule

How did British rule affect the Indian Villages: Ruling the Countryside

- The Company had become the Diwan, but it still saw itself primarily as a trader.

- But at the same time, the Bengal economy was facing a deep crisis due to Company’s unholy revenue collection. In 1770 a terrible famine killed ten million people in Bengal. About one-third of the population was wiped out.

- Now, most Company officials began to feel that investment in the land had to be encouraged and agriculture had to be improved.

- This resulted in the introduction of many land-revenue systems like Zamindari, Mahalwari, and Ryotwari.

Permanent Settlement (Zamindari)

- The Company introduced the Permanent Settlement in 1793. Cornwallis was the Governor-General of India at that time. By the terms of the settlement, the rajas and taluqdars were recognised as zamindars.

- They were asked to collect rent from the peasants and pay revenue to the Company. The amount to be paid was fixed permanently – it was not to be increased ever in future.

- The Permanent Settlement, however, created problems. Company officials soon discovered that the zamindars were in fact not investing in the improvement of land.

- The revenue that had been fixed was so high that the zamindars found it difficult to pay. Anyone who failed to pay the revenue lost his zamindari. Numerous zamindaris were sold off at auctions organised by the Company.

- In the 19th century, the situation changed. Now the market rose a bit. But Company never gained because it could not increase a revenue demand that had been fixed permanently.

- On the other hand, in the villages, the cultivator found the system extremely oppressive.

Mahalwari settlement

- The company needed more money but the permanently fixed revenues couldn’t help them in this regard.

- So in North-Western Provinces of the Bengal Presidency (most of this area is now in Uttar Pradesh), an Englishman called Holt Mackenzie devised the new system which came into effect in 1822.

- He felt that the village was an important social institution.

- Under his directions, collectors went from village to village, inspecting the land, measuring the fields, and recording the customs and rights of different groups.

- The estimated revenue of each plot within a village was added up to calculate the revenue that each village (mahal) had to pay.

- This demand was to be revised periodically, not permanently fixed.

- The charge of collecting the revenue and paying it to the Company was given to the village headman, rather than the zamindar. This system came to be known as the mahalwari settlement.

Ryotwari / Munro System

- Earlier Captain Alexander Read and later Thomas Munro felt that in the south there were no traditional zamindars.

- The settlement, they argued, had to be made directly with the cultivators (ryots ) who had tilled the land for generations.

- Their fields had to be carefully and separately surveyed before the revenue assessment was made.

Indigo plantation

- By the 13th century, Indian indigo was being used by cloth manufacturers in Italy, France and Britain to dye cloth. However, only small amounts of Indian indigo reached the European market and its price was very high.

- By the end of the 18th century, Britain began to industrialise, and its cotton production expanded dramatically, creating an enormous new demand for cloth dyes.

- While the demand for indigo increased, its existing supplies from the West Indies and America collapsed for a variety of reasons.

- Britain took it as an opportunity to persuade or force Indian cultivators to grow Indigo.

How was indigo cultivated?

- There were two main systems of indigo cultivation – nij and ryoti .

- Nij: the planter produced indigo in lands that he directly controlled. He either bought the land or rented it from other zamindars and produced indigo by directly employing hired labourers.

- Ryoti system: the planters forced the ryots to sign a contract, an agreement (satta). Those who signed the contract got cash advances from the planters at low rates of interest to produce indigo. When the crop was delivered to the planter after the harvest, a new loan was given to the ryot, and the cycle started all over. The price they got for the indigo they produced was very low and the cycle of loans never ended.

- The planters usually insisted that indigo be cultivated on the best soils in which peasants preferred to cultivate rice. Indigo, moreover, had deep roots and it exhausted the soil rapidly. After an indigo harvest, the land could not be sown with rice.

The “Blue Rebellion” and After

- In 1859 thousands of ryots in Bengal refused to grow indigo. As the rebellion spread, ryots refused to pay rents to the planters and attacked indigo factories.

- Even zamindars were unhappy with the increasing power of the planters so they supported ryots.

- Worried by the rebellion, the government brought in the military to protect the planters from assault, and set up the Indigo Commission to inquire into the system of indigo production.

- It declared that indigo production was not profitable for ryots. The Commission asked the ryots to fulfil their existing contracts but also told them that they could refuse to produce indigo in future.

- After the revolt, indigo production collapsed in Bengal.

How did British rule affect the Cities: Ruling the Colonial Cities & Urbanisation

- The European Commercial Companies had set up base in different places early during the Mughal era: the Portuguese in Panaji in 1510, the Dutch in Masulipatnam in 1605, the British in Madras in 1639 and the French in Pondicherry (present-day Puducherry) in 1673.

- From the mid-eighteenth century, there was a new phase of change. Commercial centres such as Surat, Masulipatnam and Dhaka, which had grown in the 17th century, declined when trade shifted to other places.

- Company agents settled in Madras in 1639 and in Calcutta in 1690. Bombay was given to the Company in 1661 by the Portuguese. The Company established trading and administrative offices in each of these settlements.

- After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and the trade of the English East India Company expanded, colonial port cities such as Madras, Calcutta and Bombay rapidly emerged as the new economic capitals.

Colonial records and urban history

- From the early years, the colonial government was keen on mapping. This knowledge provided better control over the region and helped to gauge commercial possibilities and plan strategies of taxation.

- From the late 19th century onwards the British handed over some responsibilities to elected Indian representatives to collect municipal taxes.

- The growth of cities was monitored through regular headcounts. By the mid-19th century, several local censuses had been carried out in different regions. The first all-India census was attempted in 1872. Thereafter, from 1881, decennial (conducted every ten years) censuses became a regular feature. This collection of data is an invaluable source for studying urbanisation in India.

- However, the census process and its corresponding enumeration were riddled with ambiguity. The classification failed to capture the fluid and overlapping identities of people. for eg: a person who was both an artisan and a trader were difficult to classify. People themselves were never able to provide their real profession.

Trends of change

- After 1800, urbanisation in India was slow-moving.

- 19th century up to the first two decades of the 20th, the proportion of the urban population to the total population in India was extremely low and had remained stagnant.

- However, there were significant variations in the patterns of urban development in different regions. The smaller towns had little opportunity to grow economically. Calcutta, Bombay and Madras, on the other hand, grew rapidly and soon became sprawling cities.

- Earlier these three centres functioned as collection depots for the export of Indian manufacturers such as cotton But now become the entry point for British-manufactured goods and for the export of Indian raw materials.

- The introduction of railways in 1853 meant a change in the fortunes of towns. Economic activity gradually shifted away from traditional towns which were located along old routes and rivers.

What Were the New Towns Like?

- By the 18th century Madras, Calcutta and Bombay had become important ports.

- The English East India Company built its factories (i.e., mercantile offices) there and because of competition among the European companies, fortified these settlements for protection.

- Indian merchants, artisans and other workers who had economic dealings with European merchants lived outside these forts in settlements of their own.

- After the 1850s, cotton mills were set up by Indian merchants and entrepreneurs in Bombay, and European-owned jute mills were established on the outskirts of Calcutta. This was the beginning of modern industrial development in India.

- Calcutta, Bombay and Madras grew into large cities, but this did not signify any dramatic economic growth for colonial India as a whole.

- India never became a modern industrialised country, since discriminatory colonial policies limited the levels of industrial development.

- The majority of the working population in these cities belonged to what economists classify as the tertiary sector.

- There were only two proper “industrial cities”: Kanpur, specialising in leather, woollen and cotton textiles, and Jamshedpur, specialising in steel.

Urbanisation, a change since 1857

- After the Revolt of 1857 British attitudes in India was shaped by a constant fear of rebellion.

- They felt that towns needed to be better defended, and white people had to live in more secure and segregated enclaves and new urban spaces called “Civil Lines” were set

- White people began to live in the Civil Lines. Cantonments – places where Indian troops under European command were stationed – were also developed as safe enclaves. These areas were separate from but attached to the Indian towns.

- From the 1860s and 1870s, stringent administrative measures regarding sanitation were implemented and building activity in the Indian towns was regulated. Underground piped water supply and sewerage and drainage systems were also put in place around this time. Sanitary vigilance thus became another way of regulating Indian towns.

Buildings in cities included forts, government offices, educational institutions, etc were often meant to represent ideas such as imperial power and nationalism.

Learn more

This article is the 3rd part of the article series on Modern Indian History. Click the link to read the 6-part framework to study modern Indian History. This is an easy-to-learn approach to master the history of modern India as a story.

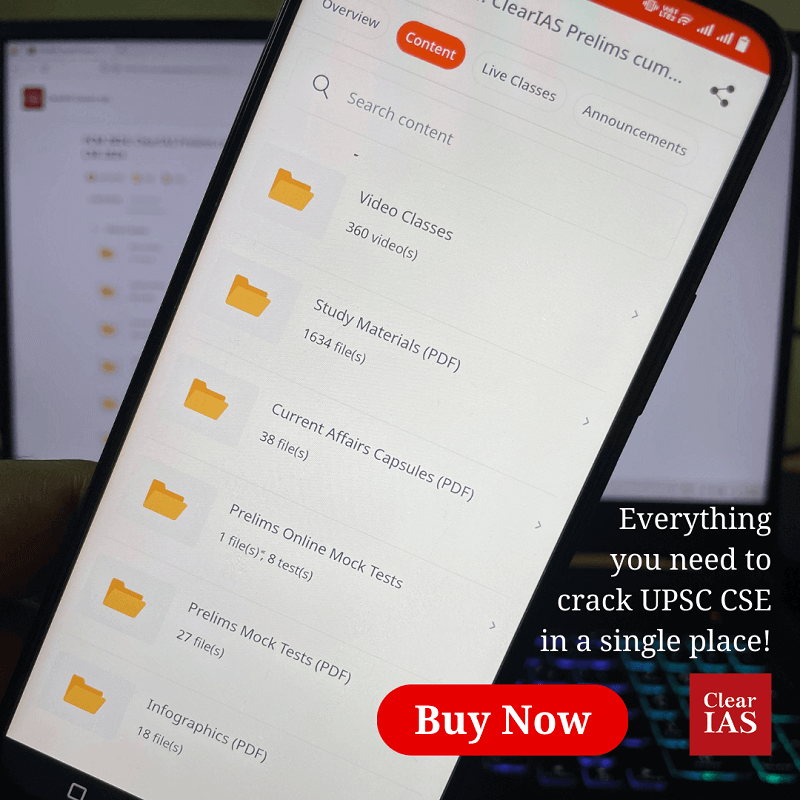

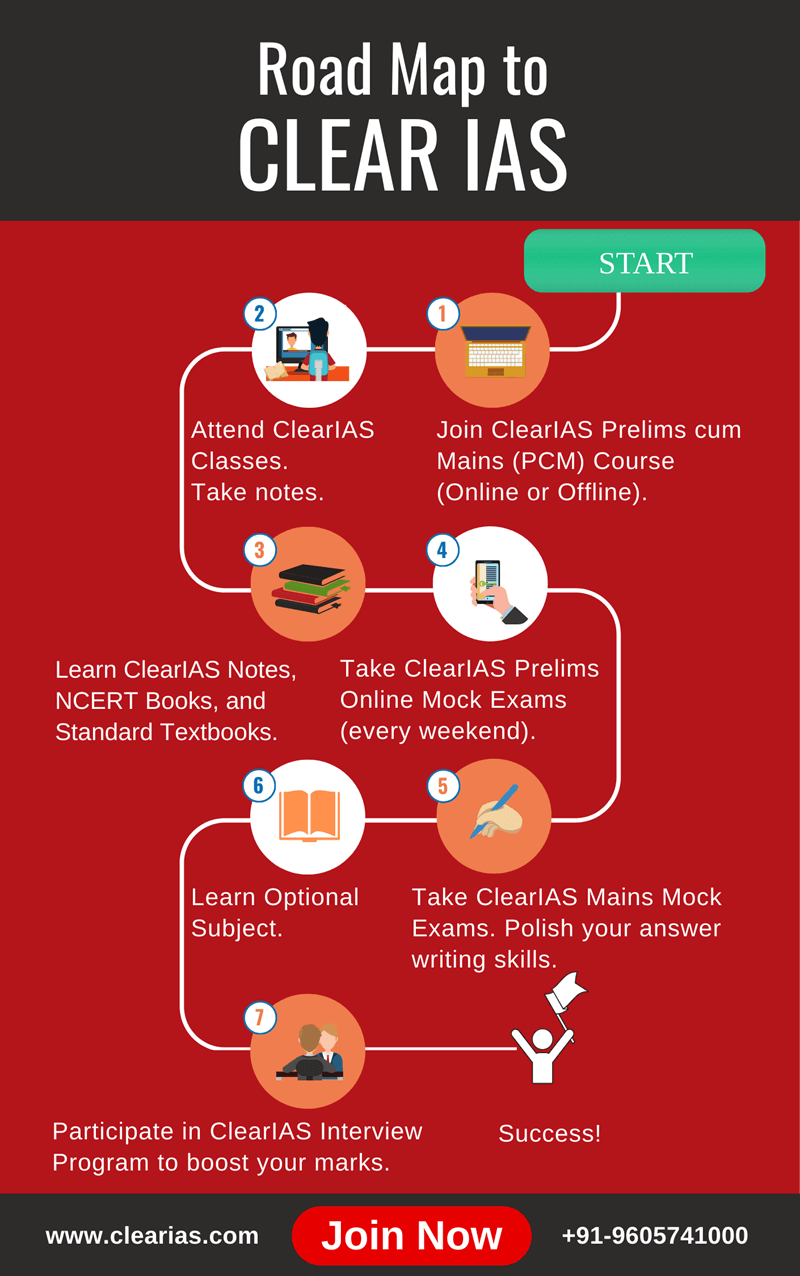

Apart from the 6-part approach, we have also published many other articles on Indian History, which can be accessed from the ClearIAS Study materials section.

Leave a Reply