Agri-food policies are crucial in sustaining and protecting soil, water, air, and biodiversity (SWAB). Read here to learn more.

Soil, water, air, and biodiversity (SWAB) are essential for maintaining the health and productivity of agricultural ecosystems and ensuring food security.

Given the impacts of agricultural practices on the environment, there is a growing emphasis on developing and implementing policies that promote sustainable farming methods while safeguarding natural resources.

Agri-food policies for protecting SWAB

In the face of growing pressures on environmental resources exacerbated by climate change, it is crucial to acknowledge the intricate relationship between food production, natural resource management and ecological sustainability.

Our agri-food policies wield immense influence in sculpting the vitality of our soil, the purity of our water and air, and the diversity of our ecosystems.

- Soil degradation, often caused by erosion, nutrient depletion, and chemical contamination, reduces the fertility and resilience of farms, hampering crop yields.

- Depletion of groundwater resulting from excessive irrigation and inefficient water management practices threatens the sustainability of agriculture by diminishing water availability for irrigation.

- Moreover, the GHG emissions from agricultural activities, such as methane from livestock and nitrous oxide from fertilizers, exacerbate climate change, leading to unpredictable weather patterns and extreme events that disrupt agrarian productivity.

- Additionally, the loss of agro-biodiversity undermines the genetic diversity of crops and reduces the resilience of agricultural ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and adverse weather conditions.

- Addressing these interconnected challenges is essential for fostering sustainable and resilient food production systems capable of meeting the needs of a growing global population while safeguarding environmental health.

Soil Conservation

Soil is a non-renewable resource that is vital for crop production.

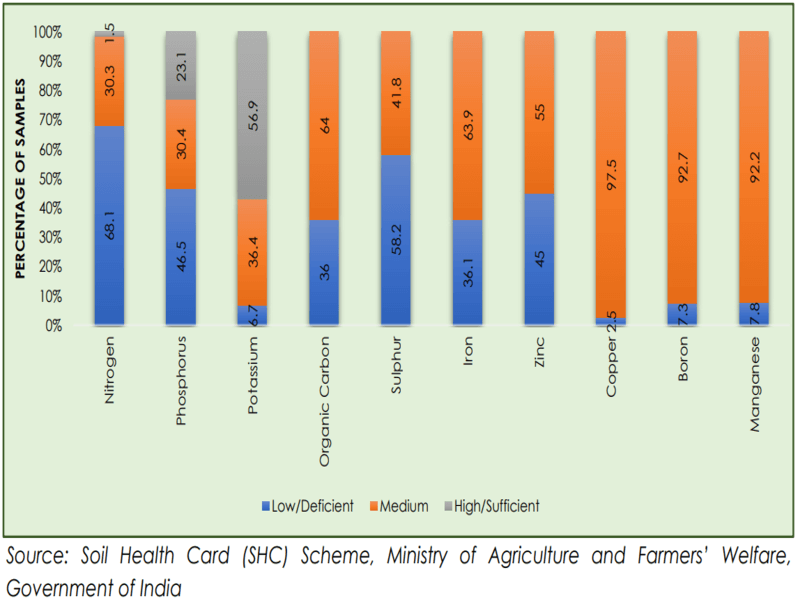

- Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) is a crucial indicator of soil health, which provides soil with its water-retention capacity, structure, and fertility.

- Research on soil degradation has revealed that the majority of soils worldwide have experienced a loss of 25-75 per cent of their original soil carbon content.

- The ideal proportion of soil organic matter should be approximately 2.5-3.5 per cent by weight in the root zone and that of soil organic carbon about 1.5- 2 per cent.

- However, many tropical soils currently contain less than 0.1 per cent SOC.

- Falling SOC in Indian soils is a cause of major concern for the agriculture sector challenging food security in India.

- Deficiency of SOC affects the productivity of soil as micro-organisms do not survive, a key factor in providing nutrients for crops

Analysis of factors driving soil degradation indicates that intensification of human activities and unsustainable management practices such as imbalance of nutrient extraction on harvested products and the native and applied nutrients, leads to nutrient mining, i.e., depletion of the organic matter in soils.

- Other factors include crop residue burning directly in the agricultural fields, destroying the available soil organic matter and soil organisms; increasing acidification of croplands driven by excessive nitrogen fertilization and unsustainable water management practices causing soil salinization.

- Further, the imbalanced use of fertilizers, weedicides, pesticides, etc., makes the soil biologically sterile, combined with the ongoing effects of climate change, have led to significant degradation of soils.

- This trend is pushing soil towards critical thresholds in its capacity to provide food, feed, and fibre for all.

Policies aimed at soil conservation focus on preventing erosion, maintaining fertility, and enhancing soil structure. These can include:

- Incentivizing the use of cover crops to reduce erosion and soil degradation.

- Promoting conservation tillage practices that minimize soil disturbance.

- Subsidizing organic farming practices that enhance soil organic matter and biodiversity.

- Establishing soil health monitoring programs to provide farmers with data for better soil management.

In India, the policy of subsidizing key fertilizers, particularly nitrogenous (N), phosphatic (P), and potassic (K) fertilizers, was initiated in the 1970s when the green revolution was still unfolding.

Given the negative externalities caused by the urea subsidy on the environment, a few alternatives to rationalise it could be:

- Switch to direct cash transfer into the accounts of farmers based on per hectare of gross cropped area, and free up the prices of these fertilisers.

- This would bring down the wide imbalance between prices of N (urea), P and K fertilisers and would incentivise farmers to use more balanced doses of N, P and K.

- Another alternative could be to bring urea under the Nutrient Based Subsidy Scheme (NBS), with a flat rate subsidy on N, P and K. This would raise the urea prices significantly.

- The soluble fertilisers, nano fertilisers, and also biofertilisers, could brought at par.

Water Management

India is categorized as a water-stressed nation due to its declining per capita water availability.

- Central Water Commission estimates that 78 per cent of water withdrawals in the country are for agricultural purposes.

- The widespread adoption of tube-well irrigation, primarily fueled by increased electricity availability for agriculture, has been the driving force behind the reduction in canal irrigation.

- The issues of depleting and deteriorating groundwater and its quality observed in the agricultural sector can be largely attributed to longstanding policies of subsidies for agricultural inputs, such as power and fertilizers, as well as price support mechanisms like Minimum Support Price (MSP) for crops like paddy and wheat, and Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP) for sugarcane.

Water scarcity and pollution are major challenges in agriculture. Effective water management policies ensure the availability and quality of water for agricultural uses while preserving aquatic ecosystems. Policies could involve:

- Implementing efficient irrigation technologies like drip or sprinkler systems to reduce water wastage.

- Regulating the use of fertilizers and pesticides to prevent water contamination.

- Supporting rainwater harvesting and water recycling practices to improve water availability.

- Establishing water user associations to manage local water resources collaboratively and sustainably.

There is a need for transforming the agriculture sector policies in line with SDG 6.4, to “Increase Water-Use Efficiency and Ensure Freshwater Supplies”.

- Reducing the area under rice cultivation by at least one million hectares in states like Punjab and Haryana, where 99 per cent of rice fields rely on flood irrigation methods and redirect rice cultivation to eastern India.

- Implementing Direct Income Support on a per-hectare basis offers a promising solution to address the policies of free power supply, coupled with deregulating power tariffs to reflect market dynamics and implementing universal metering.

- Water-saving irrigation technologies like micro-irrigation (such as drip and sprinkler systems) promoted under the Government of India’s Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojna are imperative as a precursor to sustainable agricultural intensification.

Climate change

Agriculture can contribute to air pollution through the release of particulates, chemicals, and greenhouse gases. Policies to improve air quality may include:

- Regulating and monitoring ammonia and methane emissions from livestock operations.

- Promoting agroforestry and integrated pest management (IPM) to reduce the need for synthetic inputs.

- Encouraging renewable energy sources in agricultural practices, reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

- Carbon farming incentives that reward practices reducing carbon emissions or enhancing carbon sequestration.

Over the period 1950-2018, average temperatures in the country have increased by 0.70 C while the summer monsoon precipitation (June to September) over India has declined by around 6 per cent from 1951 to 2015, with notable decreases over the Indo-Gangetic Plains and the Western Ghats.

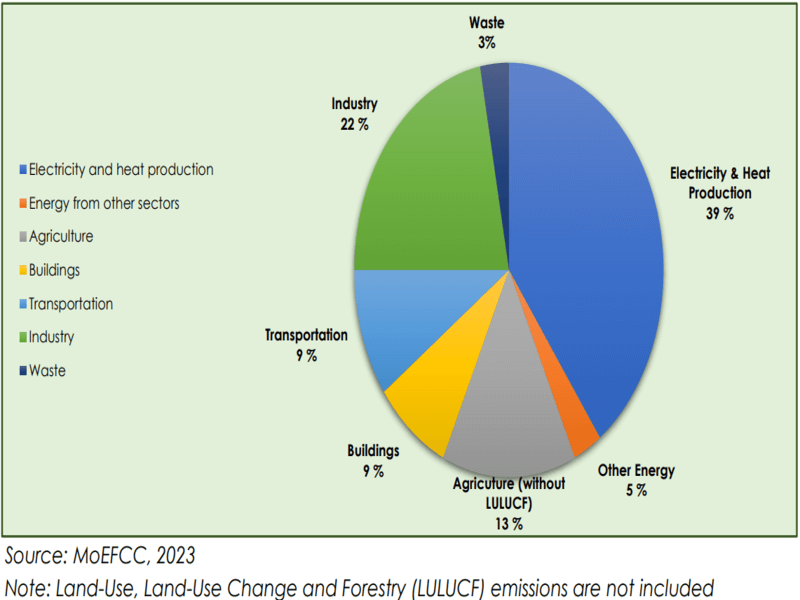

- The agriculture sector is affected most adversely by climate change impact but at the same time, it also adds to the climate crisis.

- The sector contributed about 13.44 per cent of the total Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions in India in 2019.

If India moves quickly to low-carbon agriculture, the country can at least partially mitigate the damage.

- By shifting from price subsidy to income subsidy for direct cash transfer to farmers on per hectare basis, farmers can purchase the fertilizers as per their requirement (including micronutrient fertilizers) and choice (that include bio-inputs, vermicompost etc.).

- Premium minimum support price (MSP) for low-carbon crops.

- The country’s agriculture contributes to 13 per cent of the world’s agriculture emissions and thus has significant scope for trading carbon under a carbon trading system, where one carbon credit unit is equivalent to one tonne of carbon dioxide emissions.

Biodiversity Preservation

Agriculture subsidies can impact negatively on biodiversity, directly (e.g. when diverse cropping pattern is converted to mono-cropping) and indirectly (e.g. climate change, which then impacts biodiversity).

- Impacts can be immediate (e.g. land change, crop change, biomass burning), arise over time (e.g. pollution, eutrophication, leaching etc.) and sometimes can be felt acutely by future generations (e.g. climate change).

- Overall net impacts may be less clearly negative where the incentive creates both positive and negative impacts (e.g. food subsidy achieving food security objectives but encouraging mono-cropping of wheat rice cultivation through assured procurement of MSP).

Biodiversity is crucial for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem resilience. Policies to protect biodiversity in agricultural landscapes might encompass:

- Protecting and restoring habitats within agricultural lands, such as hedgerows, buffer strips, and wetlands.

- Supporting diversified and rotational cropping systems that mimic natural ecosystems.

- Funding for biodiversity-friendly practices such as wildlife corridors and pollinator support initiatives.

- Legal frameworks that protect endangered species and regulate the introduction of invasive species.

Instead of further incentivizing biodiversity harmful subsidies, India should assess options to repurpose subsidy policies to neutralize their effects on biodiversity which is also critical to the resource mobilization needed to implement the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

- Agro-biodiversity services need to be valued and mechanisms for green credits or biodiversity credits need to be developed so that producers can get incentives for opting for crops and practices that favour agrobiodiversity.

Cross-Cutting Policies

Some policies can simultaneously address multiple aspects of SWAB, such as:

- Agro-ecological zoning to guide land use based on environmental sensitivity and suitability.

- Education and extension services to disseminate knowledge on sustainable practices.

- Integration of SWAB goals into national agricultural policies and international agreements.

- Public-private partnerships to leverage resources and expertise from different sectors.

Why in the news?

ICRIER released a report on Agri-Food Trends and Analytics which sheds light on the influence of agri-food policies on India’s agricultural production and emphasizes on synergy of SWAB for sustainable food systems.

Conclusion

Effective implementation of these policies requires robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, stakeholder engagement, and adequate funding.

Furthermore, adaptive management approaches are crucial to respond to changing environmental conditions and scientific advancements.

Adopting these agri-food policies not only helps protect soil, water, air, and biodiversity but also contributes to the resilience of food systems against climate change and other global challenges. This approach ensures long-term sustainability, aligning with global sustainability goals and commitments.

Related articles:

- Sustainable agri-food systems

- Agriculture export policy

- Food security in India

- Green agriculture

- National Pest Surveillance System (NPSS)

-Article by Swathi Satish

Leave a Reply